Next year, on 9 July 2024, forty years will have passed since Andrei Șerban’s first staging of Turandot at the Royal Opera House. This production of the last opera by Giacomo Puccini is still being performed in London, to sold-out houses, with audiences willing to stay long into the night, unable to stop applauding.

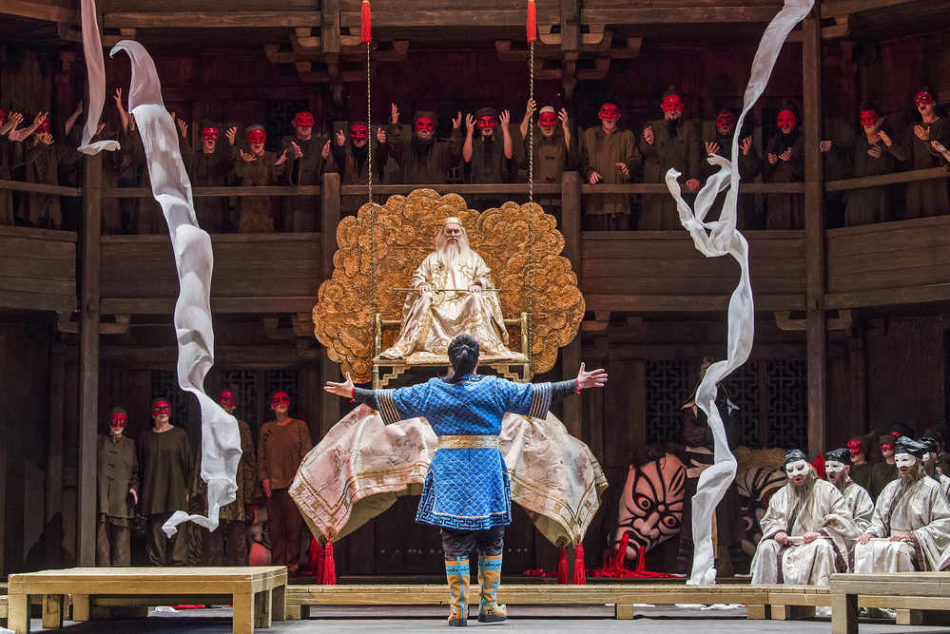

Opening photograph: Tristram Kenton, 2017, Royal Opera House

Șerban’s Turandot has been playing for decades now, and this classical, poised production – initially placed, like all of the great Romanian artist’s stagings, under the sign of controversy – remains a benchmark of beauty, one that nearly rivals the soloists themselves. (Not so Antonio Pappano, however, who in 2023, from the conductor’s podium at the ROH, formed a perfect partnership with the director’s talent.)

How has a production lasted for so many years? Andrei Șerban himself is astonished by the longevity of his own staging, an amazement officially recorded in the British opera house’s programme booklet:

“Andrei Serban, a Romanian-American opera and theatre director, works all over the world. He is both surprised and delighted that his production of Turandot is still revived at the Royal Opera House after almost 40 years since its creation.” 1.

Yet opera lovers who come to the great auditorium at Covent Garden simply for joy, harmony, and beauty – the emotional stones from which the pedestal of art is endlessly raised – are not surprised at all. On the contrary, they spread the word to those who have not yet seen this marvel, proof being that the production is sold out from one end of the season to the other.

On 13 March 2023, Alexandra Coghlan, a distinguished journalist of the British cultural press, wrote:

‘Deeply, unfashionably, unapologetically splendid, this Turandot is a parting gift from another era (…) See it. Once it’s gone, we’ll never see the like again. ‘ 2

With the same thought in mind, I left the performance on 20 March 2023. Under Antonio Pappano’s baton, the orchestra and chorus sang almost impeccably – faultless, if not dazzling – alongside Anna Pirozzi (Turandot), Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha (Liù), and Russell Thomas (Calaf). Standing apart musically was the utterly enchanting trio of Ping, Pang, and Pong, who conquered the stage with every appearance through the performances of Hansung Yoo, Aled Hall, and Michael Gibon – the latter a young artist from the Jette Parker Programme, which from the autumn of 2023, also includes a Romanian soprano, the talented Valentina Pușcaș.

The story of Andrei Șerban’s Turandot, however, did not begin in London. The Royal Opera House’s first performance of this production did not take place at Covent Garden, but in Los Angeles, where the company was invited to the Olympic Arts Festival. The premiere was held at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, a hall with over 3,000 seats, featuring Plácido Domingo as Calaf, the Welsh soprano Gwyneth Jones as Turandot, and Yoko Watanabe as Liù, conducted by Sir Colin Davis.

I searched for the earliest American reviews and discovered – yet again – that not only in our country but everywhere in the world there exist critics of vision, knowledge, and intuition, alongside critics whom history ought to shame.

John Rockwell’s New York Times review of 16 July 1984 is highly enthusiastic about the staging- more reserved regarding the performances – but records an unmistakable triumph: “The audience was in rapture!”

“‘What commanded attention in the ”Turandot” was Mr. Serban’s work, which had its questionable elements but which at its frequent best proved truly thrilling. (…)

Mr. Serban and his designer, Sally Jacobs, chose instead to set all the action within what looked like a cross between the Globe Theater and a Kabuki stage. When we needed to see the moon, a huge painted disk was lowered from the flies. The crowds took their places along the balconies at the back, which served to focus and project their already bracing impact. And the lighting effects (by F. Mitchell Dana) that could be achieved with smoke and the filtering capabilites of the various lattice screens and doors were really sumptuous”. ³

One day later, on 17 July 1984, Thor Eckert Jr.- later to found the Academy of Vocal Arts (AVA) – published a review titled “Turandot at the Olympics – a gala evening, a musical disaster”, a critique positioned at the opposite pole. I quote several passages below, with longer excerpts from the original article included in the footnotes:

“The entire enterprise should have been closed down at the first planning meeting, especially given director Andrei Serban’s unhappy operatic track record – at least on this continent.”

“At no point during the evening did Serban clarify the plot, the relationships between the characters, or the power structures of the drama.”

“Turandot, the icy quintessence of an aristocratic ruler, prances around in white makeup and kimono peignoirs of uncommon ugliness. Prince Calaf, the mysterious wanderer destined to melt the icy Princess, appears to have strolled in from a touring production of ”The Mikado.” Sally Jacobs’s overbearingly ugly unit set is, one surmises, meant to be a Chinese version of the Old Globe Theatre, although it looks more like the tiered courtyard of some shabby Chinese inn. The chorus sits in two balconies all night – robbing us of the chance to encounter this fine singing-acting ensemble in full glory.”⁴

The production returned again and again, reviews piling up in an archive of praise. I will stop at just one more article, from 1994, when David Blewitt wrote in The Stage (24 November):

“Andrei Șerban’s production for the ROH of Puccini’s Turandot continues to astound. I don’t mind how long it stays in the repertoire as long as revival directors treat it with the fervour and respect it deserves..

One of its extraordinary qualities is that changes of conductor and cast seem not to undermine the staging’s mesmerising ability to draw one into the cruelty and spectacle, to disconcert one’s emotional empathy”.⁵

As an added reason for pride and wonder, the performance Blewitt reviewed featured the Romanian tenor Corneliu Murgu as Calaf:

“Corneliu Murgu cuts a fine figure as Calaf, going for the music with a will. His clarion tenor is rousing. Subtle he is not.”⁶

Andrei Șerban: It is a miracle that the production still pleases audiences today—perhaps even more than at the beginning.

Beyond their subjectivity, beauty, impoliteness, or grace, the reviews written over the years are also revealing in one crucial respect: nothing essential has been altered in the directorial structure. Andrei Șerban’s Turandot at the Royal Opera House endures, forty years after its conception, with the same resounding success and the same defining elements – controversial or not.

The chorus still occupies the multi-level stage – because no one, absolutely no one except Andrei Șerban seems capable of filling every corner of the stage with details that invite you to see the performance a second, third, or tenth time. The costumes remain unchanged – horrendous to some, splendid to others (taste is not up for debate, but good taste and bad taste undeniably exist). And Liù’s catafalque still crosses the stage at the end, as shattering as it was forty years ago, providing the emotional counterpoint that I believe was necessary- both theatrically and morally – to remind us, the ungrateful inhabitants of this earth, how easily we despise and forget unconditional love, even as we pretend to seek it everywhere, while those loves that test our very humanity continue to lure us, almost hypnotically, into the illusion of triumph

There is, however, no true triumph in love. In opera, yes. Andrei Șerban is one of those creators who should know both the secrets and the taste of triumph -yet he continues to doubt, as emerges from the answers he gave me during a night of writing across the ocean, from America to England.

Alice Năstase Buciuta: How do you explain, Mr. Andrei Șerban, that such a production still lasts and makes audiences applaud deliriously at the end of the performance? Why does it remain on the great stage of Covent Garden and in the hearts of London’s refined opera lovers?

Andrei Șerban: For many years now, the management at Covent Garden has not invited me to lead the revivals of Turandot, perhaps out of fear that I would change too much. The assistants faithfully reproduce the original version, and it is a miracle that the production continues to please audiences today- perhaps even more than at the beginning.

A.N.B.: If you were given the chance, the time, and the budget, would you nonetheless change anything in the staging you created for Turandot?

Andrei Șerban: Yes- I would change everything! In the future I will create a new Turandot at the Athens Opera, in the ancient Herodes Atticus Theatre, completely different from the London one.

A.N.B.: Do you have other productions that are (almost) as long-lasting? Which ones, and where should we go to see them?

Andrei Șerban: My productions of The Tales of Hoffmann, Manon, and Werther are revived almost constantly at the Vienna State Opera, while Lucia di Lammermoor has been playing at the Bastille for thirty years and was revived again in 2023. A production that was equally booed and adored at the beginning is now considered classic -almost traditional. How tastes change!

A.N.B.: After so many years of success, recognition, occasional contestation and applause, do you still have doubts and emotions about your productions? Do you still suffer when something does not turn out well, do you still erupt in anger over mistakes?

Andrei Șerban: Nothing is ever perfect, but you have to live with the illusion that one day you will reach a high C. If you are satisfied with where you are, it is a sign of regression.

A.N.B.: Do you think you will ever change?

Andrei Șerban: I try to change every day, to find something fresh, something new… I do not succeed, but I keep searching- I have no choice. Life makes no sense if you do not search and allow yourself to be surprised by something you do not yet know. When you think you know, you are in danger of stagnation. I do want to believe that I have changed radically over time. But your question gives me something to ponder: perhaps, seen from the outside, I have not changed at all. That would be tragic.

* Footnotes

1. “Andrei Serban, a Romanian-American opera and theatre director, works all over the world. He is both surprised and delighted that his production of Turandot is still revived at the Royal Opera House after almost 40 years since its creation.” (The Royal Opera House, 2022-2023, Turandot- Programme)

2. ‘Deeply, unfashionably, unapologetically splendid, this Turandot is a parting gift from another era (…) See it. Once it’s gone, we’ll never see the like again. ‘ (Alexandra Coghlan – https://inews.co.uk/culture/turandot-royal-opera-house-review-well-never-see-the-likes-of-antonio-pappanos-splendid-version-again-2205134 )

3. ‘What commanded attention in the ”Turandot” was Mr. Serban’s work, which had its questionable elements but which at its frequent best proved truly thrilling. ”Turandot” is a score that in its short 60 years of life has accumulated an encrusted layer of staging cliches, from the huge staircase down which the ice princess must descend, to her cumbersome, jewel-laden robe, to the pervasive postcard chinoiserie.

Mr. Serban and his designer, Sally Jacobs, chose instead to set all the action within what looked like a cross between the Globe Theater and a Kabuki stage. When we needed to see the moon, a huge painted disk was lowered from the flies. The crowds took their places along the balconies at the back, which served to focus and project their already bracing impact. And the lighting effects (by F. Mitchell Dana) that could be achieved with smoke and the filtering capabilites of the various lattice screens and doors were really sumptuous.

There was also a constant onslaught of ornate props and really wonderful costumes, in a giddy Oriental potpourri; Miss Jacobs, who is English but who has lived in Los Angeles since 1967, includes among her credits the Peter Brook/Royal Shakespeare Company ”Midsummer Night’s Dream” and ”Marat/Sade,” and this ”Turandot” is no comedown.

Mr. Serban was also very good at staging the encounters between Turandot and Calaf. For the riddle scene, he had Gwyneth Jones in a striking blood-red kimono with black clouds, and Placido Domingo in a quilted blue jacket with decorated knee boots. Miss Jones skulked and crouched like a Kabuki player, and Mr. Domingo writhed and exulted, more conventionally operatic but nearly as convincing.

Some of Mr. Serban’s specific choices could be questioned, from the archly stylized striking of the gong (more a prissy poking, actually) at the end of Act I to the reappearance of Liù’s corpse on a funeral cart at the very end. But most of his ideas were conceived and achieved with real flair and fidelity to the lurid spirit of the work. The audience was adorational.’ (John Rockwell, New York Times, 16 July 1984, “Royal Opera Presents 3 Works in Los Angeles” )

4. “This entire venture should have been scrubbed at the first planning session, particularly given director Andrei Serban’s unfortunate track record in opera – at least on these shores.

Puccini’s final opera is his most exotic, colorful score, full of passion and panoply, love and barbarity. What we got on stage was a buffoon show that ignored the music altogether. Mr. Serban has chosen to set this in some pan-Asian theatrical milieu that purports to borrow on elements of No, Peking Opera, Kabuki, and other forms of Far Eastern performance. Serban has taken certain stereotypical fragments of these highly controlled, concentrated disciplines and tossed them carelessly onto a disheveled stage. At no moment in the course of this evening does Serban illuminate the plot, the character relationships, or the power structures of the drama.

Turandot, the icy quintessence of an aristocratic ruler, prances around in white makeup and kimono peignoirs of uncommon ugliness. Prince Calaf, the mysterious wanderer destined to melt the icy Princess, appears to have strolled in from a touring production of ”The Mikado.” Sally Jacobs’s overbearingly ugly unit set is, one surmises, meant to be a Chinese version of the Old Globe Theatre, although it looks more like the tiered courtyard of some shabby Chinese inn. The chorus sits in two balconies all night – robbing us of the chance to encounter this fine singing-acting ensemble in full glory”, (Thor Eckert Jr., https://www.csmonitor.com/1984/0717/071712.html )

5. “Andrei Șerban’s production for the ROH of Puccini’s Turandot continues to astound. I don’t mind how long it stays in the repertoire as long as revival directors treat it with the fervour and respect it deserves.

One of its extraordinary qualities is that changes of conductor and cast seem not to undermine the staging’s mesmerising ability to draw one into the cruelty and spectacle, to disconcert one’s emotional empathy. “ (David Blewitt, The Stage, 24 November 1994)

6. ‘Corneliu Murgu cuts a fine figure as Calaf, going for the music with a will. His clarion tenor is rousing. Subtle he is not.’ (David Blewitt, The Stage, 24 November 1994)